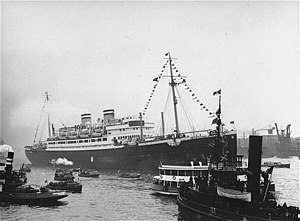

MS St. Louis

St. Louis in the port of Hamburg[1]

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Germany | |

| Name | St. Louis |

| Owner | Hamburg America Line |

| Port of registry | Hamburg |

| Builder | Bremer Vulkan, Bremen, Germany |

| Laid down | June 16, 1925 |

| Launched | August 2, 1928 |

| Maiden voyage | March 28, 1929 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Scrapped in 1952 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | ocean liner |

| Tonnage | 16,732 GRT; 9,637 NRT |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 72 ft (22 m) |

| Depth | 42.1 ft (12.8 m) |

| Decks | 5 |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 2 × screws |

| Speed | 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) |

| Capacity | 973 passengers: 270 cabin class, 287 tourist class, 416 third class |

| Sensors and processing systems |

|

MS St. Louis was a diesel-powered ocean liner built by the Bremer Vulkan shipyards in Bremen for Hamburg America Line (HAPAG). She was named after the city of St. Louis, Missouri. She was the sister ship of Milwaukee. St. Louis regularly sailed the trans-Atlantic route from Hamburg to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and New York City, and made cruises to the Canary Islands, Madeira, Spain; and Morocco. St. Louis was built for both transatlantic liner service and for leisure cruises.[2]

In 1939, during the build-up to World War II, the St. Louis carried more than 900 Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany intending to escape antisemitic persecution. The refugees first tried to disembark in Cuba but were denied permission to land. After Cuba, the captain, Gustav Schröder, went to the United States and Canada, trying to find a nation to take the Jews in, but both nations refused. He finally returned the ship to Europe, where various countries, including the United Kingdom, Belgium, the Netherlands and France, accepted some refugees. Many were later caught in Nazi roundups of Jews in the occupied countries of Belgium, France and the Netherlands, and some historians have estimated that approximately a quarter of them were killed in death camps during the Holocaust.[3] These events, also known as the "Voyage of the Damned", have inspired film, opera, and fiction.

Background and early years

[edit]Under construction number 670, St. Louis was launched on August 2, 1928, at the Bremer Vulkan in Bremen-Vegesack. She was 174.90 m long and 22.10 m wide and was measured with 16,732 GRT. Four double-acting six-cylinder two-stroke diesel engines (MAN type, built under license from Bremer Vulkan) each with an output of 3150 hp gave her a speed of 16.5 knots (30.6 km/h). Her sister ship, Milwaukee, was launched on February 20, 1929.

St. Louis left Hamburg on March 28, 1929, for her maiden voyage to New York City, and was then mainly used in the North Atlantic service from Hamburg to Halifax, and then to New York. She also made cruises of 16–17 days each to the Canary Islands, Madeira and Morocco, especially in autumn and spring. From 1934 she was also chartered in the summer by the Office for Travel, Hiking and Holidays (RWU) of Strength Through Joy (KDF) to travel to Norway with 900 holidaymakers at a time.

The "Voyage of the Damned"

[edit]Under the command of Captain Gustav Schröder, St. Louis set sail from Hamburg to Havana, Cuba on May 13, 1939, carrying 937 passengers, most of them Jewish refugees[4][5] seeking asylum from Nazi persecution in Germany.

Captain Schröder was a German[6] who went to great lengths to ensure dignified treatment for his passengers.[7] Food served included items subject to rationing in Germany, and childcare was available while parents dined. Dances and concerts were put on, and on Friday evenings, religious services were held in the dining room. A bust of Hitler was covered by a tablecloth. Swimming lessons took place in the pool. Lothar Molton, a boy traveling with his parents, said that the passengers thought of it as "a vacation cruise to freedom".[8]

On reaching Cuba, she anchored at 04:00 on May 27 at the far end of the Havana Harbor, but was denied entry to the usual docking areas. The Cuban government, headed by President Federico Laredo Brú, refused to accept the foreign refugees, although they held legal tourist visas to Cuba, as laws related to these had been recently changed. On May 5, 1939, four months before World War II began, Havana had abandoned its pragmatic immigration policy, by virtue of decree 937, which "restricted entry of all foreigners except U.S. citizens, unless authorized by Cuban secretaries of state [and] subject [to] a bond of US $500."[9] None of the passengers knew that their landing permits had been invalidated a few weeks earlier.[6]

After the ship had been in the harbor for five days, only 28 passengers were allowed to disembark in Cuba.[10][11] Twenty-two were Jews who had valid United States visas; four were Spanish citizens and two were Cuban nationals, all with valid entry documents. The last admitted was a medical evacuee, a desperate passenger who attempted suicide, and was allowed hospitalization in Havana.[4]

Records show American officials Secretary of State Cordell Hull and Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau had made efforts to persuade Cuba to accept the refugees, quite like the failed attempts by the American Jewish "Joint" Distribution Committee, which pleaded with the government.[11] After most passengers were refused landing in Cuba, Captain Schröder directed St. Louis and the remaining 907 refugees towards the United States.[12] He circled off the coast of Florida, hoping for permission from authorities to enter the United States. Neither Hull nor U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt chose to intervene to admit the refugees. Captain Schröder considered running St. Louis aground along the coast to allow the refugees to escape but, acting on Hull's instructions, United States Coast Guard vessels shadowed the ship and prevented this.[13]

After St. Louis was turned away from the United States, a group of academics and clergy in Canada tried to persuade Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King to provide sanctuary to the passengers.[14] The ship could have reached Halifax, Nova Scotia in two days.[15] The director of Canada's Immigration Branch, Frederick Blair, was hostile to Jewish immigration and persuaded the head of government on June 9 not to intervene.

As Captain Schröder negotiated and schemed to find passengers a haven, conditions on the ship declined. At one point he made plans to wreck the ship on the British coast to force the government to take in the passengers as refugees. He refused to return the ship to Germany until all the passengers had been given entry to some other country. US officials worked with Britain and European nations to find refuge for the Jews in Europe.[11] The ship returned to Europe, docking at the Port of Antwerp (Belgium) on June 17, 1939, with the 908 passengers.[16][17]

The British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain agreed to take 288 (32 percent) of the passengers, who disembarked and travelled to the UK via other steamers. After much negotiation by Schröder, the remaining 619 passengers were also allowed to disembark at Antwerp. 224 (25 percent) were accepted by France, 214 (23.59 percent) by Belgium, and 181 (20 percent) by the Netherlands. The ship returned to Hamburg without any passengers. The following year, after the Battle of France, and the Nazi occupations of Belgium, France, and the Netherlands in May 1940, all the Jews in those countries were subject to high risk, including the recent refugees.[18][19]

Based on the survival rates for Jews in various countries during the war and deportations, historians have estimated that 180 of the St. Louis refugees in France, 152 of those in Belgium and 60 of those in the Netherlands survived the Holocaust.[20] Including the passengers who landed in England, of the original 936 refugees (one man died during the voyage), roughly 709 survived the war and 227 died.[21][11] Later research tracing each passenger has determined that 254 (29.2%) of those who returned to continental Europe were murdered during the Holocaust.

Of the 620 St. Louis passengers who returned to continental Europe, we determined that eighty-seven were able to emigrate before Germany invaded western Europe on May 10, 1940. Two hundred fifty-four passengers in Belgium, France, and the Netherlands after that date died during the Holocaust. Most of these people were murdered in the killing centers of Auschwitz and Sobibór; the rest died in internment camps, in hiding or attempting to evade the Nazis. Three hundred sixty-five of the 620 passengers who returned to continental Europe survived the war. Of the 288 passengers sent to Britain, the vast majority were alive at war's end.[22]

Legacy

[edit]After the war, the Federal Republic of Germany awarded Captain Gustav Schröder the Order of Merit. In 1993, Schröder was posthumously named as one of the Righteous Among the Nations at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Israel.[6]

A display at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., tells the story of the voyage of the MS St. Louis. The Hamburg Museum features a display and a video about St. Louis ship in its exhibits about the history of shipping in the city. In 2009, a special exhibit at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia, entitled Ship of Fate, explored the Canadian connection to the tragic voyage. The display is now a traveling exhibit in Canada.[23]

In 2011, a memorial monument called the Wheel of Conscience was produced by the Canadian Jewish Congress, designed by Daniel Libeskind with graphic design by David Berman and Trevor Johnston.[24] The memorial is a polished stainless steel wheel. Symbolizing the policies that turned away more than 900 Jewish refugees, the wheel incorporates four inter-meshing gears, each showing a word to represent factors of exclusion: antisemitism, xenophobia, racism, and hatred. The back of the memorial is inscribed with the passenger list.[25] It was first exhibited in 2011 at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, Canada's national immigration museum in Halifax. After a display period, the sculpture was shipped to its fabricators, Soheil Mosun Limited, in Toronto for repair and refurbishment.[26]

In 2012, the United States Department of State formally apologized in a ceremony attended by Deputy Secretary William J. Burns and 14 survivors of the incident.[27] The survivors presented a proclamation of gratitude to various European countries for accepting some of the ship's passengers. A signed copy of Senate Resolution 111, recognizing June 6, 2009, as the 70th anniversary of the incident, was delivered to the Department of State Archives.[27]

In May 2017, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced the Government of Canada would offer a formal apology in the country's House of Commons for its role in the fate of the ship's passengers.[28] The apology was issued on November 7, 2018.[29]

Later career

[edit]MS St. Louis was adapted as a German naval accommodation ship from 1940 to 1944. She was heavily damaged by the Allied bombings at Kiel on August 30, 1944. The ship was repaired and used as a hotel ship in Hamburg in 1946. She was sold and scrapped at Bremerhaven in 1952.[30][citation needed]

Notable passengers

[edit]- Arno Motulsky (1923–2018), medical geneticist[31]

- Frederick Reif (1927–2019), physicist at University of California, Berkeley and Carnegie Mellon University[32]

- Erich Dublon (1890-1942), whose writing regarding his experience of the ship was published.[33]

Representations

[edit]- Jan de Hartog's play Schipper naast God (1942), translated in English as "Skipper next to God" (1945)

- Voyage of the Damned (1974), a nonfiction account by Gordon Thomas and Max Morgan-Witts

- Voyage of the Damned (1976), a film directed by Stuart Rosenberg adapted from the Thomas/Morgan-Witts book

- Julian Barnes's novel A History of the World in 10½ Chapters (1989) recounts the trials of the MS St. Louis Jews in the chapter "Three Simple Stories"

- Bodie and Brock Thoene's 1991 novel Munich Signature

- Chiel Meijering composed an opera, St. Louis Blues (1994)

- Denied Entry: A Survivor's Story of Fate, Faith, and Freedom (2011), an autobiography and commentary by Philip S. Freund. ISBN 1-45-635148-6

- To Hope and Back by Kathy Kacer (2011) is a young adult nonfiction account of two children's experience on the voyage. ISBN 1-92-692040-6

- Leonardo Padura's novel Herejes (2013) centers on the St. Louis incident. ISBN 8-48-383755-2

- Nilo Cruz's play Sotto Voce (2014), explores the tragedy of the ship's passengers in the present

- The German Girl (2016), a novel by Armando Lucas Correa. ISBN 1-50-1121146

- Refugee (2017), a young adult novel by Alan Gratz. ISBN 0-54-588087-4

- Die Reise der Verlorenen, 2018 play by Daniel Kehlmann

- The Good Ship St. Louis, 2022 play by Philip Boehm

- The St. Louis Refugee Ship Blues, Art Spiegelman recounts a sad story 70 years later. by Art Spiegelman

See also

[edit]- SS Navemar, designed for 28 passengers, which carried 1,120 Jewish refugees to New York in 1941

- MV Struma, a schooner chartered to carry Jewish refugees that was torpedoed and sunk by a Soviet submarine on 5 February 1942

- MV Mefküre, a schooner carrying Jewish refugees that was torpedoed and sunk by a Soviet submarine on 5 August 1944

- Komagata Maru, a merchant ship carrying Asian migrants that was denied entry to Canada in 1914

- SS Quanza, which carried over 300 refugees including at least 100 Jews to America and Mexico in 1940

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Photo Archives United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". Archived from the original on June 29, 2016. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ "MS St. Louis German ocean liner". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Madokoro, Laura (August 9, 2021). "Remembering the Voyage of the St. Louis". Active History.

- ^ a b "Voyage of the St. Louis". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ^ Rosen, p. 563.

- ^ a b c "The Righteous Among The Nations: Gustav Schroeder". Yad Vashem. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Levine, p. 105.

- ^ Levine, pp. 110–11.

- ^ Levine, p. 103

- ^ Levine, p. 114.

- ^ a b c d Rosen, Robert (July 17, 2006). Saving the Jews (Speech). Carter Center (Atlanta, Georgia). Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ^ "The Voyage of the St. Louis" (PDF). American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. June 15, 1939. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Holocaust Memorial Day Trust | The SS St Louis". Retrieved May 2, 2024.

- ^ "What was the Coast Guard's role in the SS St. Louis affair, often referred to as "The Voyage of the Damned"?". United States Coast Guard History. December 21, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2022.

- ^ "Maritime Museum Exhibit on Tragic Voyage of MS St. Louis". Government of Nova Scotia. November 5, 2010. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ^ George Axelsson, "907 Refugees End Voyage in Antwerp", New York Times, 18 June 1939

- ^ Levine, p. 118.

- ^ Rosen, pp. 103, 567.

- ^ "The Tragedy of the S.S. St. Louis". Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ^ Thomas and Morgan-Witts (1974). Voyage of the Damned. New York, Stein and Day. ISBN 9780812816945.

- ^ Rosen, pp. 447, 567 citing Morgan-Witts and Thomas (1994) pp. 8, 238

- ^ Scott Miller and Sarah Ogilvie (2010). Refuge Denied: The St. Louis Passengers and the Holocaust. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 174–75. ISBN 9780299219833.

- ^ "Traveling Exhibit: MS St. Louis Ship of Fate" Archived June 30, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Maritime Museum of the Atlantic

- ^ Studio Daniel Libeskind Archived July 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, daniel-libeskind.com, 19 January 2011; retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ Taplin, Jennifer (January 21, 2011). "Perpetual Memorial of Regret". Metro News Halifax. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ "Exhibitions", Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, pier21.ca; accessed 12 September 2014.

- ^ a b Eppinger, Kamerel (September 26, 2012). "State Department apologizes to Jewish refugees". shfwire.com. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ "Trudeau to offer formal apology in Commons for fate of Jewish refugee ship MS St. Louis". Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- ^ "Trudeau apologizes for Canada's 1939 refusal of Jewish refugee ship". November 7, 2018. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ "M/S St. Louis, Hamburg America Line". www.norwayheritage.com. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ Motulsky, Arno G. (June 2018). "A German‐Jewish refugee in Vichy France 1939–1941. Arno Motulsky's memoir of life in the internment camps at St. Cyprien and Gurs". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 176 (6): 1289–1295. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.38701. PMC 6001526. PMID 29697901.

- ^ "Obituary: Frederick Reif / Educator, author and researcher at Carnegie Mellon University". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ "United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". Collections Search. May 22, 1939. Retrieved November 17, 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Levine, Robert M. (1993). Tropical Diaspora: The Jewish Experience in Cuba. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. p. 103. ISBN 9781558765214.

- Miller, Scott; Sarah A. Ogilvie (2006). Refuge Denied: The St. Louis Passengers and the Holocaust. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-21980-2. OCLC 64592065.

- Rosen, Robert (2006). Saving the Jews: Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Holocaust. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 978-1-56025-778-3. OCLC 64664326.

- Whitaker, Reginald (1991). Canadian Immigration Policy. Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association. ISBN 0-88798-120-8.

Further reading

[edit]- Abella, Irving; Harold Troper, None Is Too Many: Canada and the Jews of Europe 1933-1948, Toronto, ON: Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1983.

- Afoumado, Diane. Exil impossible: L'errance des Juifs du paquebot St-Louis (L’Harmattan, 2005).

- Anctil, Pierre; Alexandre Comeau. "The St. Louis Crisis in the Canadian Press: New Data on the June 1939 Incident." Canadian Jewish Studies / Études Juives Canadiennes, 31, 13–40.

- Levinson, Jay. Jewish Community of Cuba: Golden Years, 1906–1958, Nashville, TN: Westview Publishing, 2005. (See Chapter 10)

- Morgan-Witts, Max; Gordon Thomas (1994). Voyage of the Damned (2nd, revised (first in 1974) ed.). Stillwater, Minnesota: Motorbooks International. ISBN 978-0-87938-909-3. OCLC 31373409.

- Ogilvie, Sarah; Scott Miller. Refuge Denied: The St. Louis Passengers and the Holocaust, Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006.

- Sampson, Pamela. No Reply: A Jewish Child Aboard the MS St. Louis and the Ordeal That Followed, Atlanta, GA, 2017

- Lawlor, Allison. The Saddest Ship Afloat: The Tragedy of the MS St. Louis, Nimbus Publishing, 2016. ISBN 978-1771083997

External links

[edit]- Robert Rosen, "Carter Center Library Speech" on "The S.S. St. Louis", July 17, 2006, Saving the Jews: Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Holocaust

- "St. Louis affair", US Coast Guard's official FAQ

- "American Responses to the Holocaust - St. Louis", U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

- "The Story of the S.S. St. Louis (1939)" American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives

- "SS St Louis: The ship of Jewish refugees nobody wanted" BBC News

- Matthias Loeber, “Swept back into the unseen vastness of the sea” - Fritz Buff's account of his voyage aboard the ST. LOUIS, May and June 1939, in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, March 15, 2021, https://dx.doi.org/10.23691/jgo:article-266.en.v1

- 1928 ships

- 1939 in Canada

- 1939 in Cuba

- 1939 in Judaism

- 1939 in the United States

- International maritime incidents

- International response to the Holocaust

- Jewish emigration from Nazi Germany

- Ocean liners

- Refugees in Canada

- Ships of the Hamburg America Line

- The Holocaust and the United States

- Aid for Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany